When I reflect on the past 18 months at EOH, I can only liken it to what the women and men who have summited Mount Everest may have experienced. You stand at the bottom looking up and wonder how you will manage the 3.3km vertical distance through snowfields, crevasses, cliff faces and strong winds with very little oxygen. At any time a new storm could arrive — and then there’s the realisation that once you are at the summit, you are only halfway through the ordeal.

I have climbed many mountains, but nothing quite like this. Each day you are faced with something new; each day you need to make new decisions and perhaps change course as you get more information. EOH provides integral system and technology solutions to many government departments and large corporates, and we needed to save as many jobs as possible. Balancing this with the imperative to be transparent was more gruelling than you could imagine.

While our legal counsel and I presented evidence at the Zondo commission, we had a full team behind us who had shouldered the burden of the corruption that had been perpetrated by a few former senior employees. The members of this team were like our Sherpas, ensuring we got up and down the mountain safely. You need to have Sherpas you trust implicitly, and ours worked tirelessly to put in place the processes that characterise the well-governed and sustainable EOH of today. It is always worth remembering: businesses are not corrupt, people are.

This whole process has also strengthened my faith in corporate SA, which was largely prepared to listen to us. People listened to what happened, listened to our plans and actions to rectify the situation, and gave EOH time to prove we had removed the rot. Many people were available for advice and support.

Would I do it all again? I grapple with this. It was largely a few rogue former employees, aided by leadership and directors turning a blind eye, that came close to wiping out the livelihood of 10,000 staff and their families. The legacy of corruption does not disappear overnight after you share the findings of the investigation. There are fines and penalties to be paid for the malfeasance of former managers and directors, increased risk rates charged and heightened efforts by suppliers to secure payment for long-outstanding obligations. Understandably so. However, this does make the journey to recovery longer and harder.

These things are akin to a blizzard while trying to reach the top of Everest. Just as the summit is in sight, the storm closes in and you need to change course or retreat for a while. As the money has long left the company, this extra effort largely falls on the 10,000 remaining employees. In the end, saving the jobs of many EOH people has made the journey more than worthwhile. It is the feeling you get when you have reached the end of a climb, look back and remember a wonderful experience, the trials of the last 18 months forgotten.

We have often discussed whether going the business rescue route might have meant a quicker and easier resolution of all these issues. It may have meant the SA Revenue Service, Special Investigating Unit, JSE, lenders and creditors would have collaborated to save the company rather than making “withdrawals” and adding to the stress. Clearly this route has other implications, especially reputationally, but it may have proved a clear weather climb. In my view, this represents a flaw in the current business structures globally, especially as we try to generate and save jobs.

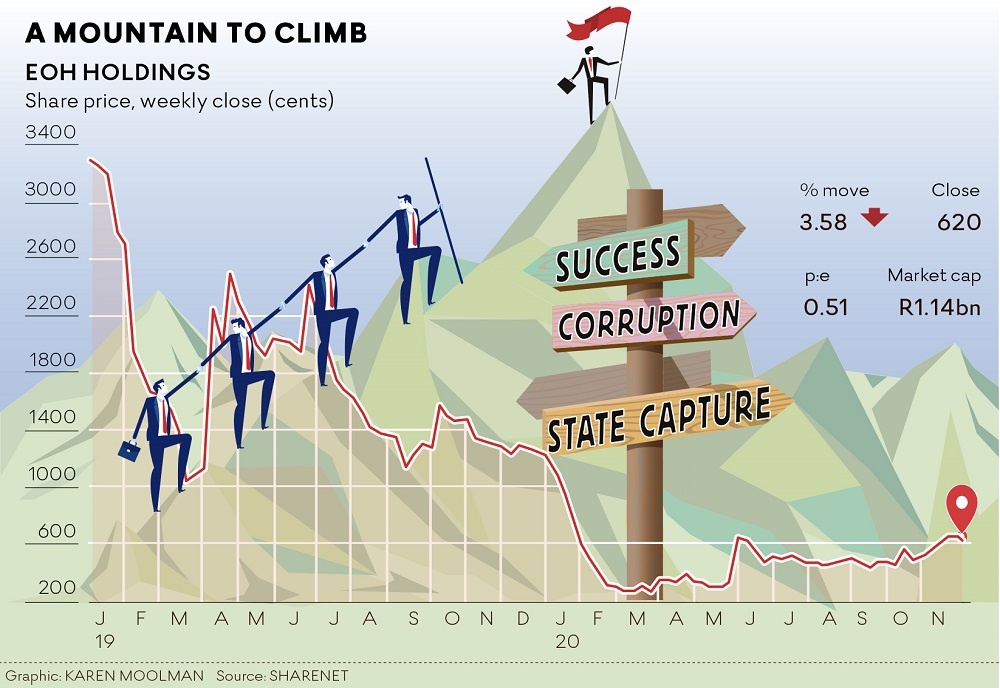

Another important insight for me is that while being listed is a source of capital for growth, there should be more restrictions on who can actually list. When you are a small-cap stock with a few large investors (EOH has five significant investors), trading in the shares is very lumpy. There are lots of technical reasons for this, but it means the stock is very volatile and is affected by every piece of information. In March 2019, when we acknowledged the bribery and corruption that had taken place and announced we were writing off a few billion rand, the share price jumped 131% in a single day, a record for the JSE.

The issue with this is that it makes it difficult for investors to easily get in or out of the stock on an acceptable basis. Second, it allows for short sellers to make easy money on the stock market on negative news. This really disadvantages investors such as pensioners who do not trade daily. A possible solution would be to limit daily and total short positions to a percentage of the daily traded volume or market capitalisation. The JSE did this after the single stock futures debacle in 2008/2009, when it realised that existing regulations had serious shortcomings. It was a simple fix and has been largely successful.

A further enhancement would be for listed companies to receive a King Code adherence certificate (somewhat like a BEE-level certificate) from the JSE. This would look at board independence, executive powers, delegation of authority, quality of board (and subcommittee) papers and minutes, internal audit reports and progress in closing down audit points, to mention a few. The banks could perform a similar review when making lending decisions.

Most of the blame has been levelled at EOH the legal entity, in effect incriminating all staff, and yet little has been done by the regulating bodies to sanction the actual perpetrators. I believe we need open and transparent dialogue and a concomitant relationship between business, financial institutions and bodies such as the Institute of Directors SA, the SA Institute of Chartered Accountants, the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors and the JSE. This is not currently the case. By going this route, we could work seamlessly together and drive accountability even through the red tape and bureaucracy. Having power in the absence of keeping those in power accountable caused much of our downfall.

Corruption almost stole the very essence of what makes EOH a great company. But more importantly, corruption steals the very essence of what a lot of people in our country fought for, for so long. They fought for equality, and unfortunately corruption is removing the very possibility of equality from their fingertips.

We are happy this chapter is now behind us and trust the prosecuting authorities will use the findings to ensure the perpetrators of the crime against EOH get due justice. Now we can get down to the real business of EOH — to grow Africa’s leading technology business ethically and sustainably.

Van Coller is EOH CEO. He recently presented evidence to the commission of inquiry into allegations of state capture.

This article was first published on BusinessLIVE on 02 December 2020.